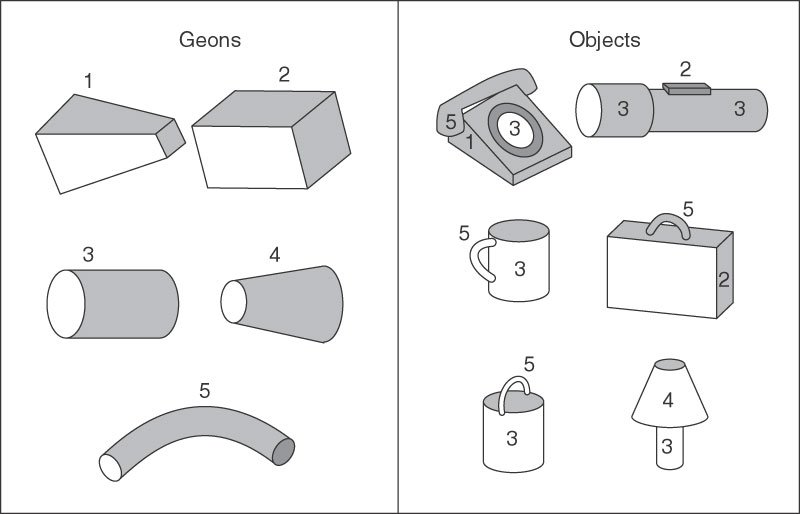

In 1987 Irving Biederman constructed the recognition-by-component theory, where he argued that people are able to recognise objects by separating them into geons – the object’s main component parts. Geons are based on basic 3-dimensional shapes (cones, cylinders, etc.) which can be joined up in various arrangements to form a virtually unlimited number of psychical objects.

We like simple. And that has its reasons in biology. Dave Pollard in his blog argues that our brains are severely limited by nature in what they are capable of understanding. Our natural and social systems are complex, unpredictable, resistant to cause-and-effect analysis. Once we create a (simplified) theory for ourselves about something, it’s hard for others to convince us otherwise. So for our first three million years on Earth we accepted that mystery and adapted to living in the unknown, yet resisting change whenever we can.

Pollard argues that the need for a more sophisticated brain is only as old as civilisation — ten to thirty millennia, which is not enough time for the biological evolution to occur. Our cultural and cognisant evolution are therefore constrained by our biological evolution — our outmoded, rudimentary brains. For some years now we’ve been trying to develop artificial intelligence to evolve faster and to improve quality of our lives and workplaces, but turns out, we can only imagine and architect intelligence of the kinds we see around us, making current AI level just a copy of our own intelligence, prone to errors and biases. If we are to let AI help us make life-or-death decisions, we’d better find the way to filter it from our own fallouts.

Generation One Size

We try to superhuman ourselves, causing cognitive dissonance between productivity and laziness by creating all possible devices and out-of-box solutions, which impose choice (with our permission to go on autopilot). Dinner tomorrow? Here is top top 3 Japanese restaurants near you. Summer music vibes? Let Spotify choose for you.

Are those choices the best you could have made consciously?

I don’t think so.

After all, what do we need to keep in our heads that we can’t find on our phones? Airplanes and cars can now autopilot. Costs can be optimised. Even doctors replace an encyclopaedic knowledge with a knowledgeable e-encyclopedia. (I experienced it myself on my visit in the GP).

It is no longer an embarrassment when you don’t know something. Instant knowledge check online became socially acceptable and now, the witty is the one, who finds the answer on Google faster. We can spend less and less thought executing more and more. But what if too little thinking happens a little too much?

Labelling humans

All our lives we work around patterns and labels. I think similar simplification pattern happens when we try to categorise people that we know by the profession they perform, or skills they posses. We just don’t like information overflow. Two variables, personJob and personName is all we want to be able to categorise someone and store them in our mind, so we can reach it once we need them. John from the accounting, Marta, the cleaner..

That’s why we strive so hard to be seen as experts at something.

We live in a society where we are hard-wired to fit people in to neat, perfect little boxes. We categorise people as soon as we see them. Our world is obsessed with labels because we find it difficult to comprehend things that don’t fit into the pre-made boxes that society has provided us with.

Audrey Arbogast

It’s somehow true that your work defines you but it’s also true that you define what you want to work on. And that’s what most people forget (but that’s a subject for a separate thread). It’s often hurtful but people judge you through prism of your work.

The good thing is – you can take control over how other people see you and how you want them to see you.

As simple as it should be, but not more

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler. […] The goal … is to make the wonderful and the complex understandable and simple, but not less wonderful. If the result is only partially rewarding this can be wholly blamed upon … the complexity of the real world.”

J.D. Sargan

No wonder, then, we aren’t happy. The ideology of unlimited choice has made us dumb. We turn to convenience and let ourselves be led in return for a peace of mind. We would have become paralysed otherwise.

In 2004 an American psychologist Barry Schwartz published a book called The Paradox of Choice – Why More Is Less where he argued that eliminating consumer choices can greatly reduce anxiety for shoppers. And it’s true not only for shopping choices. It’s as true in dating or career choices.

What is potentially lost is time spent being able to combine ideas, new angles, concepts, and locations. This sense of delayed implementation does not allow time for ideas to “simmer” in our heads. We tend to just react more rather than think. And our brain extension – mobile devices do not help with that either. Turn left now, go to this meeting now, and respond to this message that popped up in front of you.

As a people, we have become so accustomed to the push-button conveniences of modern life that we now crave that in all things. As a result, we’re rapidly transforming into a society that is shallow and reactive. (It’s good time for those who want to lead).

Whether we’re talking about the conflict inherent in trying to oversimplify product design, or something more important like career choices, we are increasingly ruled by laziness and emotion. This path is easier, but it is ultimately hollow.

We must never mistake simplicity for elegance.

All of us, regardless of our calling, must learn to once again embrace deep thinking, complexity, and nuance and reject the temptation to oversimplify. It’s time that we embrace a higher calling and push ourselves to thrive in a complex world.

That’s why we were brought here for.

![Start-ups and start-downs [Evoque Journey] louveciennes @flickr](https://hankka.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/bfast.jpg)

![What are you afraid of? [Evoque journey] Donnie Nunley @Flickr](https://hankka.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/12331672305_9d924d76b0_z.jpg)